When Was Settlement Allowed Beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains

NPS Photo

Survey of Rural Mountain Settlement

Archeological Investigations in Nicholson, Corbin, and Weakley Hollows

Central District, Shenandoah National Park by Audrey J. Horning, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Three hollows in the central district of the park—Corbin, Nicholson and Weakley hollows—are presently under examination in the National Park Service-sponsored study designed to inventory the material remains of the park's human past. Located on the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge, in the shadow of Old Rag Mountain in Madison County, Virginia, the three hollows were home to approximately 460 persons when Shenandoah National Park was created in the 1930s, having been continuously occupied by settlers of European descent since the late eighteenth century. Eighty-eight sites have been located in the three hollows, which cover approximately 2500 acres. The archaeological evidence from these hollows, the most apparently uniform of Blue Ridge communities, tells a story of adaptation, alteration, cultural retention, and individual agency throughout the period of settlement.

These three hollows are also best known as the subject of a 1933 sociological study entitled Hollow Folk which described the Blue Ridge dweller as "unlettered folk, sheltered in tiny mud-plastered log cabins and supported by a primitive agriculture," in communities which were "almost entirely cut off from the current of American life." Written by journalist Thomas Henry and University of Chicago sociologist Mandel Sherman, Hollow Folk left a lasting impression on the historiography of the region, and specifically upon interpretations of the park's recent past. The negative attention paid to these three hollows by Sherman and Henry, and others, makes the present examination of the material culture of Nicholson, Corbin, and Weakley Hollows a critical starting point for a revised history of the entire Shenandoah National Park region.

NPS Photo

Intensive surface collection of 15 sites in the hollows has provided a wealth of information which refutes the caricature of isolated and primitive mountain lifeways. The discovery of watches and calendars provides an obvious and visual contradiction to romantic notions about the medieval nature of the inhabitants, just as the finding of automotive parts puts the lie to statements about the isolation of mountaineers. The material record reveals that, contrary to the images promulgated by Thomas Henry and others, Blue Ridge residents did, in fact, wear shoes, cured their sore throats not only with cherry tree bark but with patent medicines, were as likely to purchase bonded liquor as homegrown products, ate their meals off of a variety of imported and domestic ceramics, listened to records on the phonograph, slept in fancy brass beds as well as on cheap metal cots, and served beverages in containers ranging from enameled tinware cups to fancy pressed glass pitchers. In short, the 'hollow folk' of the immediate prepark period owned the same types of goods which are found on archaeological sites of the same era throughout the United States—many no doubt originating from the Sears and Roebuck Company. The material record from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century serves as more than a mere refutation of the Blue Ridge caricature, revealing the choices faced and the choices made by rural people in an industrial age.

Of all the pre-park communities, Nicholson, Corbin, and Weakley Hollows probably came closest to fitting the traditional image of mountain subsistence farming. Yet subsistence strategies, and settlement patterns, differed between each hollow, and no hollow farm was entirely self-sufficient. Weakley Hollow is in reality a valley which separates the geologically-distinct Old Rag or Ragged Mountain from the main Blue Ridge. Archaeological evidence suggests that Weakley Hollow, a long valley separating the geologically-distinct Old Rag mountain from the Blue Ridge, was first settled in the 1770s, to eventually grow into the village of Old Rag, complete with a post office, two stores, two churches, and a school by the twentieth century. Residents during the previous century had capitalized upon their proximity to a through road by operating commercial sawmills, gristmills, and distilleries, all part of the hollow's archaeological heritage.

NPS Photo

Documentary and archaeological sources indicate that nearby Nicholson Hollow was settled in the 1790s, with the fertile bottomland along the Hughes River inviting intensive farming. As settlement density increased, farmers engaged in extensive landscape engineering, clearing and terracing slopes to create fertile land. Nineteenth-century agricultural censuses indicate that hollow farmers produced significant surpluses, which provided the cash necessary to purchase the diverse consumer goods evidenced in the archaeological record. While relatively rare, some hollow dwellers were also slaveholders, according to the documentary record. One house ruin in Nicholson Hollow has been tentatively identified as a slave quarter from the 1820s.

Steep and rocky Corbin Hollow did not evolve into a distinct community until the establishment of the nearby Skyland resort in 1886. Families relied upon wage labor and craft sales at Skyland, leaving themselves wide open for disaster when the Depression struck and the cameras of park promoters began clicking. The poverty in Corbin Hollow spoke for the entire park , as stark photographs circulated through the media and politicians were dragged to the hollow to gawk at the dismal condition of the natives. Yet the recently-examined material record indicates that even in Corbin Hollow, popular descriptions of mountain isolation and degeneracy were overblown. Typical assemblages range from decorative tablewares, pharmaceutical bottles and automobile parts to mail order toys, furniture, shoes, and even fragments of 78 rpm records. Far higher percentages of commercial food containers are recovered from Corbin Hollow sites than on Nicholson or Weakley Hollow sites, indicative of wage-labor subsistence. Not only did Blue Ridge residents actively participate in the national consumer culture, they made choices regarding their subsistence and economic lives, choices and decisions that changed over time and were tempered and shaped—but not determined by—the natural environment.

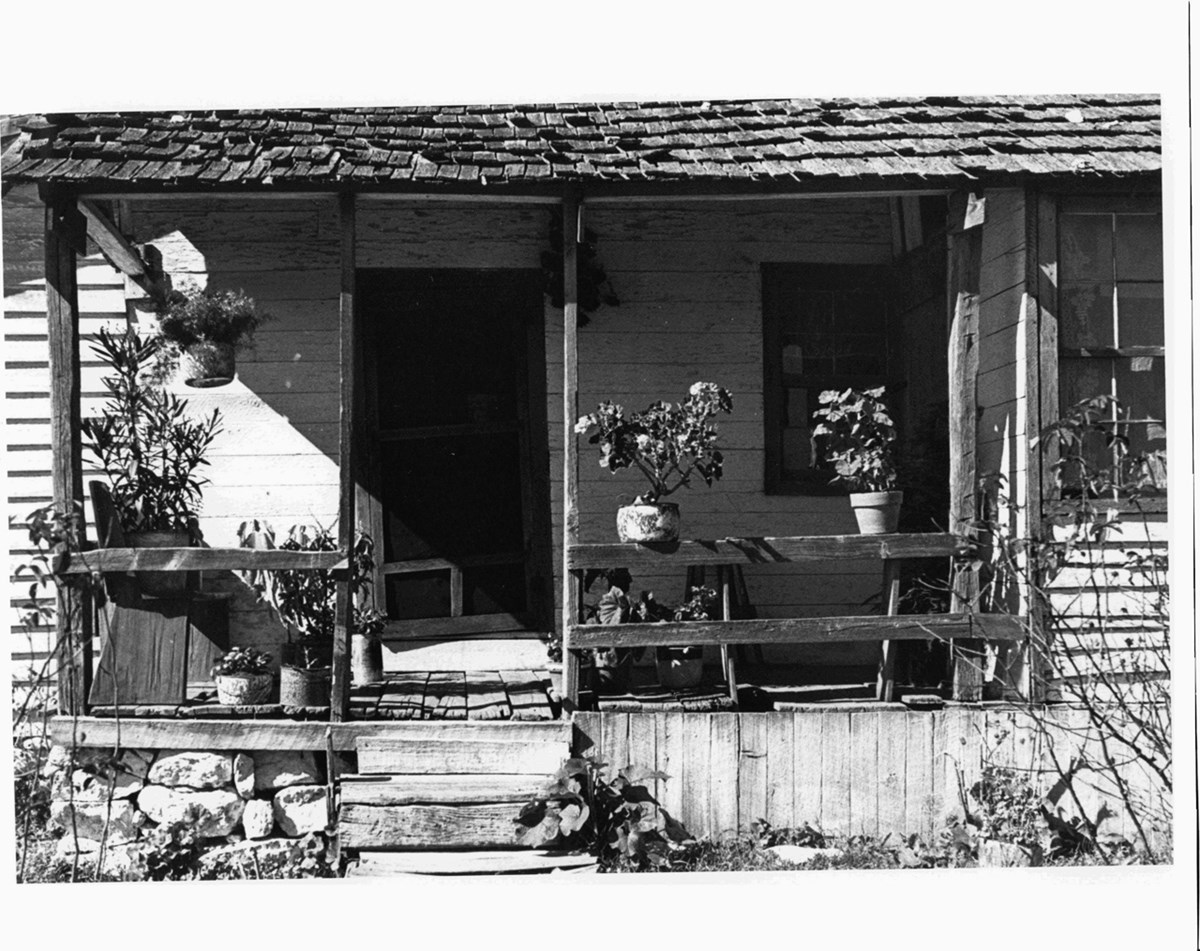

Tract records which were compiled in anticipation of land acquisition for the national park serve as an invaluable source in examining variation within and between the hollows by the early twentieth century, describing both the extent of landholdings and the types of buildings present on the properties when surveyed in the late 1920s. Outside of the tract records, there are numerous descriptions of the housing of mountain dwellers, presumed to hold true for the entirety of hollow settlement. One journalist penned a rather more creative description of housing in Old Rag:

"The rustic charm of the Shenandoah cabins is very, very rustic. Most of them are made of roughly hewn logs; the chinks are filled, somewhat nonchalantly, with mud, and the interior, in happy instances, is whitewashed. Since one rarely encounters a straight line or a true angle in the walls or ceilings, there are likely to be conspicuous discrepancies between walls and doors or window frames. No matter, says the mountaineer, and fills up the space with mud."

NPS Photo

Both archaeological evidence and the data from the tract records instead indicate that houses in the three hollows employed stone, frame, and brick as well as log. In fact, twenty-five percent of dwellings described in the tract records for the three hollows were built entirely of frame. Fifty-four percent were constructed wholly of log, while the remaining twenty-one percent employed a combination of log and frame.

The current archaeological examination of Nicholson, Corbin and Weakley Hollows makes it clear that the local cultures found in the Blue Ridge prior to the establishment of Shenandoah National Park were not the product of geographic, cultural, and familial insularity Rather, they were the result of the conscious choices made by residents throughout the period of settlement in a dynamic and continual process of borrowing, sharing, retaining, and adapting of traits between a variety of culture groups during the history of the colonial and post-colonial settlement of the region, tempered by the environment, and punctuated by economic success and failure. As elsewhere in the southern mountains, the Blue Ridge regional culture of the early twentieth century was a complex and ever-changing heritage with a multiplicity of roots.

Source: https://www.nps.gov/articles/mountain-settlements.htm

0 Response to "When Was Settlement Allowed Beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains"

إرسال تعليق